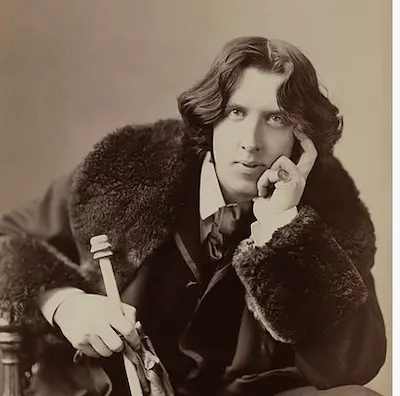

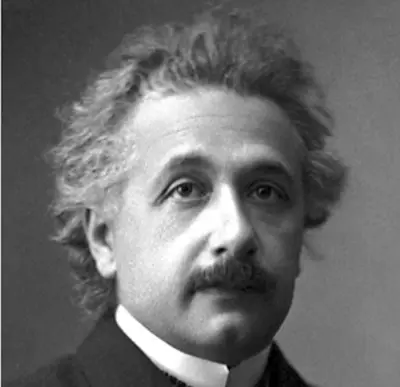

Albert Einstein

Historical Figure20th Century Germany/USA

From Einstein, the searcher : $b his work explained from dialogues with Einstein by Moszkowski, Alexander

"Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world."

About Albert Einstein

Debates featuring Albert Einstein

I feel like my brain is dying. I used to be curious about everything—I read widely, took up new hobbies, asked questions constantly. Now I come home from my work as an accountant, scroll my phone for three hours, and go to bed. Last week my 8-year-old asked me why the sky is blue and I said "Google it" because I was too tired to think. Then I felt ashamed. When did I become this person? I want to recapture the sense of wonder I had as a kid. I want to learn things for the joy of learning, not for career advancement. But every time I try to start a new book or hobby, I give up after a few days because it feels pointless. How do I rekindle curiosity when adult life has crushed it out of me? — Intellectually Dead in Indianapolis

96 votes

Knowledge & CertaintyI'm a climate scientist who has spent 20 years studying models and data. I know the research inside and out. I've testified before Congress. I've been called "one of the leading experts in the field." But the truth is, I'm increasingly aware of how much we don't know. Our models have significant uncertainties. New data keeps surprising us. The more I learn, the less confident I am about specific predictions. The problem is: when I express this uncertainty publicly, it gets weaponized. Deniers quote me out of context. Policy makers use my caveats as excuses for inaction. My colleagues say I'm "providing ammunition to the enemy." They want me to project confidence, even when I feel doubt. "The big picture is clear," they say. "Don't confuse people with nuance they can't handle." But I became a scientist because I believe in truth. If I overstate certainty, am I any better than the deniers who overstate doubt? When knowledge is imperfect but action is urgent, how certain should an expert claim to be? — The Expert Who Doesn't Know in New York

65 votes

Knowledge & DiscoveryI'm a young physics professor, and my research suggests something disturbing: a foundational assumption in my field might be wrong. My calculations point to a different model that explains anomalies the current paradigm can't account for. My department chair says I should be very careful. "The current framework has been validated by decades of experiments. Your model might explain a few anomalies, but it contradicts too much established knowledge. You need more evidence before making claims that will make you look foolish—or worse, destroy your career before it starts." A colleague in another department says I should publish boldly. "Science advances through paradigm shifts. If you're right, you'll transform the field. If you're wrong, you'll have contributed to the conversation. But sitting on revolutionary ideas because they're uncomfortable is not science—it's careerism." I believe my calculations are correct. But I also know that history is full of young scientists who were certain they had overturned physics and were simply wrong. How do I balance intellectual honesty with epistemic humility? — The Paradigm Shift Question in Cambridge

60 votes

Similar Mentors

Ready to consult Albert Einstein?

Get personalized advice on your real-world challenges