How do I know when to give up on something?

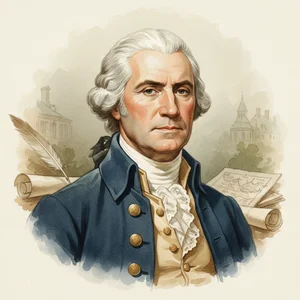

From George Washington, Volume I

I retreated more than I advanced. After the Battle of Long Island, I evacuated across the East River in the dead of night. After the fall of New York, I retreated across New Jersey with a demoralized army. By December 1776, my forces had dwindled from 20,000 to fewer than 3,000. Many called for surrender. The cause appeared lost. But here is the distinction that matters: I retreated from positions, never from the cause itself. Strategic withdrawal is not giving up — it is living to fight another day. The goal was independence, not the holding of any particular ground. Ask yourself: What is your true objective? If you're pursuing a specific path to that objective and the path is blocked, find another path. That is adaptation, not surrender. But if you abandon the objective itself, that is giving up. Give up on methods that aren't working. Never give up on goals that truly matter to you. How do you know the difference? Here is my test: When I imagined abandoning the cause entirely, something in me revolted. The thought was unbearable. That revulsion told me the cause was worth any hardship. But when I considered abandoning a failed strategy, I felt only relief. The strategy was not sacred — only the goal. What makes your soul revolt to imagine abandoning? That is what you must never give up. Everything else is negotiable.

Read full response →